Common Ground: Counseling for Multicultural Couples

Originally published on April 13, 2024 at Couple and Family Counseling

Written by By: Philip Rogers and Tomi Yamamoto

“In an increasingly multicultural world, the chances and possibilities of falling in love with someone from a different faith or cultural background is greater than ever.”

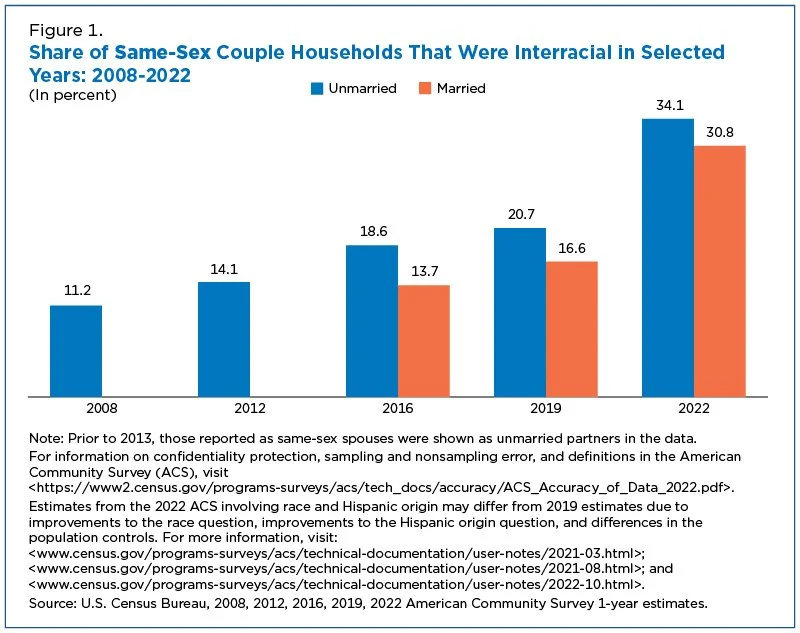

The U.S. Census Bureau (Hernandez & Hemez, 2023) found a steady increase in interracial households between 2008 and 2016 and a steep increase in 2022. Incidentally, interracial households are more prevalent with same-sex couples (34.1% unmarried and 30.8% married) than opposite-sex couples (28.6% unmarried and 18.6% married).

Furthermore, almost four in ten Americans (39%) who have married between 2010 and 2014 have a partner affiliated with a different religious group. Interfaith relationships are more common now, accounting for nearly half (49%) of unmarried, cohabitating couples (Murphy, 2015).

Interfaith relationships benefit, not just the involved couple but their immediate community and social circles in several ways (Shoaf et al., 2022):

Acceptance and tolerance: Being in an interfaith relationship often results in greater acceptance of the partner’s beliefs and of other religions and cultures. A child’s involvement in both parents’ faiths can encourage family unity and cultural harmony.

Opportunities for exploration, learning, and discovery: Interfaith relationships provide inside information and access to religious communities of the partner’s faith. Through this process, couples learn to compromise, answer questions, and even defend aspects of one’s faith.

Increased ability to identify and build on similarities: Exploration of other faiths sparks curiosity as it relates to one’s own religious affiliation, leading to discovery and celebration of religious similarities.

More religious traditions and practices: Acceptance of both partner’s faiths allows couples to enjoy more religious holidays and customs with an added element of fun.

Increased personal faith: In learning about other faiths and how to compromise with their partner, couples strengthen their individual faiths by recognizing the important aspects of their beliefs that are not open to negotiation.

Challenges

Interfaith couples experience lower rates of marital satisfaction and higher rates of instability than same-faith marriages (Shoaf et al., 2022) with issues stemming from communication, social pressure, parenting, intimacy, and microaggressions.

Communication

Communication and conflict resolution styles may diverge based on cultural background, necessitating significant work to develop a mutually acceptable method for discussing difficult topics (Seshadri et al., 2013). Communication issues can exacerbate the subsequent challenges discussed below.

Social Pressure

Individuals often avoid interfaith and cross-cultural relationships due to lack of acceptance from their social circles. The avoidance stems from parental expectations of preserving faith and cultural tradition as well as an individual’s perception of anticipated cultural clash and family reactions (Yahya & Boag, 2014). Interfaith couples may face difficulties gaining acceptance from religious or spiritual leaders in particular (Williams & Lawler, 1998; as cited in Shoaf et al., 2022). Multicultural couples’ experiences of overt and covert disapproval include being disowned by family members or family members refusing to attend their wedding (Brooks & Lynch, 2019, as cited in Greif, 2023).

A White woman married to a Latino partner, described her decision to step away from friendships due to negative judgements of their relationship:

“I have to admit, I sometimes get really angry with folks, and I cut them out of my life, which isn’t necessarily a clinically healthy thing to do, right? But that comes out of a reaction to protect myself and my family.” (Greif, 2023)

An Arab Christian male, from another study expressed:

“My parents don’t like it that I have Muslim friends… They’re just not very trusting of that religion… I probably wouldn’t ever be allowed to even date a Muslim because Catholic Christians and Muslims have had warfare… so it probably would get me kicked out of every family and extended family that I’ve got here. My parents would crucify me!” (Yahya & Boag, 2014).

An Arab female married to a man from a different cultural background but of the same faith spoke about her experience being disowned by her family:

“They (my parents) cried, they went to the hospital, they made their life miserable and my sibling’s life, because they (my siblings) live with them… unfortunately I can’t do much about it because you find yourself just being in a vicious circle. So we’re not talking to each other, my parents just think that I’m on the wrong track and I have to go back and I have to seek forgiveness from them and obey their will.” (Yahya & Boag, 2014)

Parenting

Couples planning to incorporate children into their family unit commonly encounter issues around parenting styles. Those in interfaith relationships may experience additional issues like clashing opinions on religious education and socialization for the child (Riley, 2013; as cited in Shoaf et al., 2022). Riley (2013; as cited in Shoaf et al., 2022) noted that the desire to adhere to a certain religion in raising a child can be strong, sudden, and unexpected, causing tension in the relationship.

For interracial couples, a child’s racial identity may form to match one parent and not the other. Both parents may find this outcome acceptable but may face backlash from extended family members who disagree with the child’s racial identification (Greif, 2023). Couples with biracial or multiracial children may also need to assist them in navigating a world that may not be accepting (Atkin et al., 2022).

A White woman married to an African partner described their efforts in preparing their son to handle negativity:

“We need to make sure that he sees stuff so he’s not oblivious and doesn’t set himself up. And then the other is kind of keeping his emotions in check so that he doesn’t get overly neurotic and fearful. It’s a work in progress.” (Greif, 2023)

Intimacy

Intimacy is often viewed through a Western lens, which can pathologize a non-White partner when their intersectionality (i.e., family-of-origin, immigration status, gender) is ignored (Shibusawa, 2019; as cited in Greif, 2023). Additionally, sexual difficulties can be exacerbated by multiple sets of religious expectations (Mehta, 2012).

Microaggressions

Small acts of discrimination are common lived experiences of multicultural couples. Microaggressions include being ignored when seeking service, having parentage questioned when a child has a different skin tone from a parent, one partner minimizing the racial experiences of the other partner (Greif, 2023).

An Asian woman married to a White man reflected on how she addressed microaggressions in the past:

“When it comes from a stranger, I haven’t found any successful way of handling it because I don’t know how to handle it without being confrontational. Also, I know I can’t change an individual or their way of thinking in an instant.” (Greif, 2023)

TREATMENT GOALS

Co-Constructing a Shared Belief System

Counselors should assist clients in determining which of their socially constructed cultural expectations are personally relevant and meaningful to co-create a foundation of values that meets the needs of both parties (Seshadri et al., 2013). This can help couples to center their mutual priorities and avoid being blindsided by ideological differences.

Fostering Pride, Understanding, and Respect

Treatment should focus on allowing both members of the system to build a strong sense of self and to maintain pride in their respective cultures while fostering awareness and respect regarding the culture of their partner (Greif, 2023). In order to be most effective, this self image should be based on personal values that extend beyond cultural expectations (Greif, 2023).

“Marcus [White] sees his assimilation to his wife Deborah (Mexican-Japanese) as making things easier in their relationship around going to her side of the family’s events and family parties during the holidays: (sigh) It made it easier! [laughs] Because I could join you for whatever! And if we had something going on, we were a flexible family that could get together whenever, I guess it was easier on us because of that” (Seshadri et al., 2013)

Encouraging Open Communication

Open communication, particularly regarding differences between members of the dyad, is an essential element of many successful intercultural relationships (Seshadri et al., 2013; Shoaf et al., 2022). It is of particular significance that couples be able to discuss the influence of culture on their perception of social roles based on identity, including how racial and gender privilege factor differently into both individuals’ experience (Seshadri et al., 2013; Shoaf et al., 2022).

INTERVENTIONS

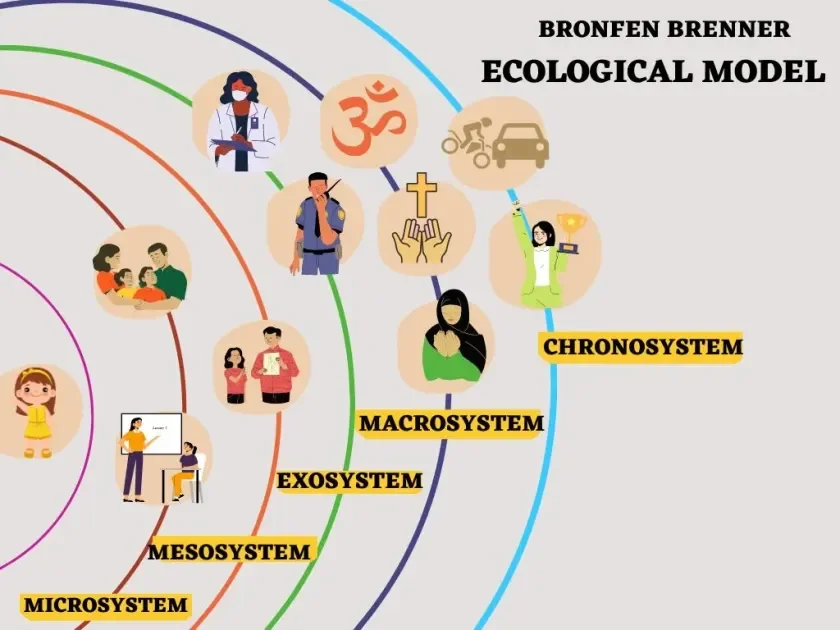

Seshadri et al. (2013) determined four ‘major strategies’ or core competencies that successful intercultural couples used to manage their differences. Below is a list of questions or concepts that apply to each of them. A counselor might explore the answers from a narrative perspective or use Bronfenbrenner’s model to expand the questions to include the context of the mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. It may be effective to incorporate elements of both approaches depending on the clients, and Feminist Family therapy could be a useful modality to utilize alongside either of these to assist in unpacking power dynamics and gender roles (Greif et al., 2022).

(a) Creating a ‘‘we’’

In what ways are you similar? How do you show one another your commitment? What are your short and long term goals? In what ways are your core beliefs compatible?

(b) Framing differences

What is the power dynamic in the relationship? Does one partner’s culture take precedence over the other? Does one partner have more privilege outside the relationship and if so, does that show up within the relationship? In what ways are you flexible for one another, how do you compromise? What kinds of efforts do you make to learn about your partner’s culture? Are there times your differences cause difficulty in the relationship?

(c) Emotional maintenance

How willing are you to discuss your partner’s feelings of discrimination regarding race and culture? When have you adapted for your partner’s comfort because of cultural, racial, or spiritual reasons? Why were you willing to do that? How do you cope when faced with prejudice?

“But when they (our children) were babies, people would ask me, ‘‘Are those your children?. .. I mean. . .people say the stupidest things, you know? And don’t even realize what they are saying. But, I just laugh it off, you can’t get mad at it’’ (Seshadri et al., 2013)

(d) Positioning in relationship to familial and societal context

Do you come from individualist or collectivist backgrounds? What do these contexts mean to each of you? How does your family and your community feel about your partner? How does it change your view of them? Are you willing to stand up for them in front of your friends, parents, or peers? How do you work together to feel confident in your relationship when others judge you? What strategies do you use to deal with criticism or discrimination in a non-reactive way?

Early Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory has been proven effective in intercultural education and could be useful in helping clients to conceptualize the ways that different systems interact and influence their lives (Eriksson et al., 2023; Tong et al., 2023). Ecological Systems Theory can be used to broaden the questions regarding the major strategies developed by Seshadri et al. (2013) beyond the microsystem by slightly modifying the theory to use the couple as the center of the system rather than the individual (Seshadri et al., 2013; Tong & An, 2023). Having established a ‘we,’ a couple can use a similar method to examine how they exist in a wider context.

Mesosystem (family and friends): How do you show your partner’s family you are curious and respectful of their culture?

Exosystem (local community): Where do you find support in your community? What kind of discrimination do you face?

Macrosystem (society, the world at large): Who do you want to be as a couple in the world? How does it differ from your role in the family?

Chronosystem (Time, life stages): How consistent are your goals and your commitment to one another? How is your identity as an interracial, intercultural, or interfaith couple informed by the history of where you live? This can be of particular interest for couples who come from backgrounds with a history of conflict.

Narrative Therapy

A couple, married or otherwise, represents two separate contexts merging to create a new, third context comprising the essential beliefs of all involved parties through equitable, mutual exploration. Dominant cultural narratives are a central concept in Narrative theory concerning the ways that we internalize ‘truths’ about ourselves and others based on their race, culture, or faith by experiencing the way media, family, and social context we are exposed to teaches us (White & Epston, 1990).

If a person is raised to believe their culture is superior and adequate for understanding the world, this could lead to cultural encapsulation and an inability to establish equality with a partner. What Narrative can offer intercultural and interfaith couples is an opportunity to re-evaluate the importance of external narratives in the context of their co-constructed ‘we’ (Seshadri et al., 2013; White & Epston, 1990).

The following quote is an example of how these concepts could be used with a Muslim and Catholic interfaith couple:

“But when both spouses take their religious accounts seriously enough to engage differences, to learn from them, and to create novel ways of worshiping together alongside the marginalized (respecting their differences, too), they are arguably imitating the unity-in-difference of the Trinity and Incarnation in the Catholic tradition, and the unity-in-difference of the Divine Names of God (70) and theological cosmology in the Islamic tradition (“Wheresoever you turn, there is the Face of God” [Qur’an 2:115]).” (Takács, 2020)

In the context of Narrative therapy, this would be an excellent example of using re-authoring to prioritize the client’s commitment to faith and to one another over external pressure and even conceptualizations of faith. The clients could use this to aid in creating a ‘we’ by defining which aspects of their faith are most important, in framing difference by defining which aspects of their faith diverge and whether they are comfortable with merging them, and in positioning to familial and societal context by determining how they will receive criticism or curiosity over this choice.

This is an example of how a counselor exhibiting cultural humility with a basic grasp of the cultures and faiths of both clients could assist in a way that a counselor who had not done that work would be unable to.

Additional Modalities

Like many therapeutic topics, this issue is incompatible with universal solutions. The two modalities discussed above were frequently represented in related literature, and the following is a list of other approaches offered by Austin (2021) that may be appropriate for a broader multicultural population:

Multicultural Counseling

Person-Centered Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Trauma-Informed Care

Solution-Focused Therapy

Spiritually Integrated Counseling

Cultural Considerations: Humility over Competence

For both the clients and the counselor, an approach grounded in cultural humility rather than aspiring to “cultural competence” is important (Beagan, 2018).

Cultural competence implies an “otherness” and can reinforce the narrative that one cultural context is dominant, and centers the comfort and confidence of the learner rather than the effectiveness of their understanding at bridging any gaps (Beagan, 2018). That being said, it is vital that the counselor pursues an understanding of the context of the clients they are working with and takes part in rigorous self-examination to avoid bias, particularly if they share a background with one member of the couple and not the other. If the couple does not feel that the counselor is adequate to this task, it is likely to negatively impact treatment outcomes (Daniel, 2024).

Additional Training Opportunities and Resources

[Article] Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (Ratts et al., 2015)

[Training] Counseling Multiracial Populations: Strengths and Challenges https://imis.counseling.org/store/detail.aspx?id=PEES19006

Lived Experiences

[Book] Boundaries of Love Interracial Marriage and the Meaning of Race by Chinyere K. Osuji

[Book] Saffron Cross: The Unlikely Story of How a Christian Minister Married a Hindu Monk by J. Dana Trent

[Blog] Cup of Jo: Three Couples on Interracial Relationships

[Blog] Daisy Butter: What It’s Like Being in an Interracial Relationship

[Blog] The Almost Indian Wife: I Never Would Have Expected To Learn This From My Interracial Relationship

[Blog] We Built Our Interfaith Marriage on a Religion of Love

[Movie] The Big Sick (fiction based on real-life experiences)

[Video] Multicultural Couples Debate on Raising Their Children | 2 Couples, 1 Couple

[Video] Stories of Interracial Love: Love that Binds – Part 1 | Part 2

References

Atkin, A. L., Jackson, K. F., White, R. M. B., & Tran, A. G. T. T. (2022). A qualitative examination of familial racial-ethnic socialization experiences among multiracial American emerging adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(2), 179-190. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1037/fam0000918

Austin, V. D. (2021). Treatment strategies and healing related to African American mental health. In M. O. Adekson (Eds.), African Americans and mental health: Practical and strategic solutions to barriers, needs, and challenges (pp. 125-134). Springer.

Beagan, B.L. (2018). A critique of cultural competence: Assumptions, limitations, and alternatives. In: C. Frisby & W. O’Donohue (Eds.), Cultural competence in applied psychology. Springer, Cham.

Daniel, S. (2024). Negotiating the challenges of an interracial marriage: An interpretive phenomenological analysis of the perception of diaspora Indian partners. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 73(1), 282–297.

Eriksson, M., Ghazinour, M., & Hammarstrom, A. (2018). Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory & Health, 16(4), 414-433. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-018-0065-6

Greif, G. L. (2023). Long-term interracial and interethnic marriages: What can be learned about how spouses deal with negativity from others. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1080/15313204.2023.2173697

Greif, G. L., Stubbs, V. D., & Woolley, M. E. (2023). Clinical suggestions for family therapists based on interviews with White women married to Black men. Contemporary Family Therapy: An international Journal, 45(3), 333-348. https://doi-org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1007/s10591-021-09629-y

Hernandez, N., & Hemez, P. (2023, November 8). Some demographic and economic characteristics of male and female same-sex couples differed. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/11/same-sex-couple-diversity.html

Mehta, S. K. (2012). Negotiating the interfaith marriage bed: Religious differences and sexual intimacies. Theology & Sexuality, 18(1), 19–41.

Murphy, C. (2015, June 2). Interfaith marriage is common in U.S., particularly among the recently wed. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/06/02/interfaith-marriage/

Seshadri, G., & Knudson, M. C. (2013). How couples manage interracial and intercultural differences: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 39(1), 43–58.

Shoaf, H. K., Hendricks, J. J., Marks, L. D., Dollahite, D. C., Kelley, H. H., & Gomez Ward, S. (2022). Strengths and strategies in interfaith marriages. Marriage & Family Review, 58(8), 675-701. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1080/01494929.2022.2093311

Takács, A. M. O. (2020). From indifference to dwelling in difference: Catholic-Muslim marriages and families and the non-hegemonic reception of Muslim migrants. Journal of Moral Theology, 9(2), 115–145.

Tong, P., & An, I. S. (2023). Review of studies applying Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory in international and intercultural education research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1233925

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton.

Yahya, S., & Boag, S. (2014). ‘My family would crucify me!’: The perceived influence of social pressure on cross-cultural and interfaith dating and marriage. Sexuality & Culture, 18(4), 759-772. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1007/s12119-013-9217-y